The upcoming verdict on the intellectual property investigation will be the real thing. Steel and aluminum are sun-set industries—the real war will be focused on innovation and technology. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (Cfius) recently blocked the Chinese merger and acquisitions (M&A) deals of Xcerra and Alibaba by deeming them “national security risks”; that is a real concern. Trump has hinted that China is a “strategic competitor.” So the trade war is more about economic competition rather than different political ideology or human rights policies. Chinese economist and politician Liu He’s absence from the very critical Third Plenum to instead travel to the U.S. highlights China’s sense of urgency regarding an imminent trade war. However, Liu He may only have the power to delay this trade war, but not prevent it. As a concession, Liu He will likely offer to further open up the Chinese market to foreign investment, but this overture will probably not be enough from Trump’s perspective. Interestingly, we have not received any media reports on whether Liu He has made any progress during his visit, which means there hasn’t been a breakthrough to report.

We have been proponents of global growth for over a year—will a looming trade war slow it down and make companies hesitant to invest? How much of this risk is priced in?

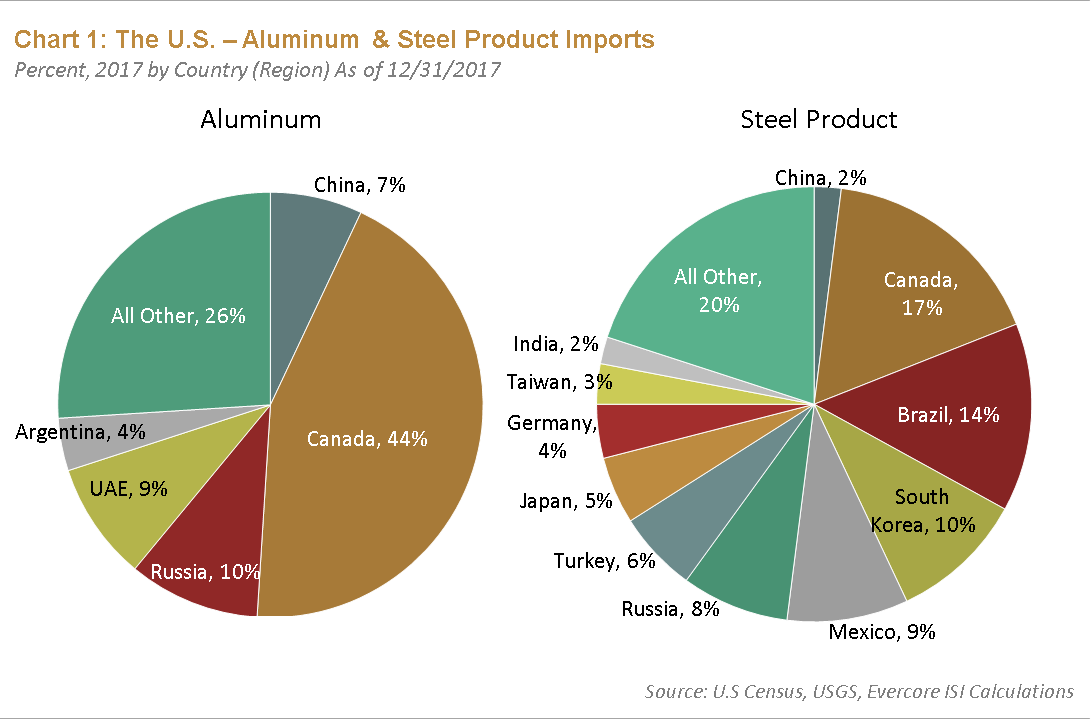

Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs—and the potential for appointing a trade hawk as his chief economic advisor—have been haunting the market since Gary Cohn announced his departure. As an investor, you can dismiss the tariff by saying it won’t impact China as much and suggest that Trump won’t rock the boat by risking a trade war. That is true if you think the tariff will stop there—then it’s no big deal. However, the real deal is yet to come. From the U.S. perspective, China’s share of U.S. steel and aluminum imports is tiny at 2% and 7% respectively. See Chart 1 below.

From the Chinese perspective, its steel exports to the U.S. have already fallen significantly due to various anti-dumping duties—another form of a protectionist tariff assessed on imports that are priced below fair market value—and therefore only make up 1.6% of total Chinese exported steel volume.

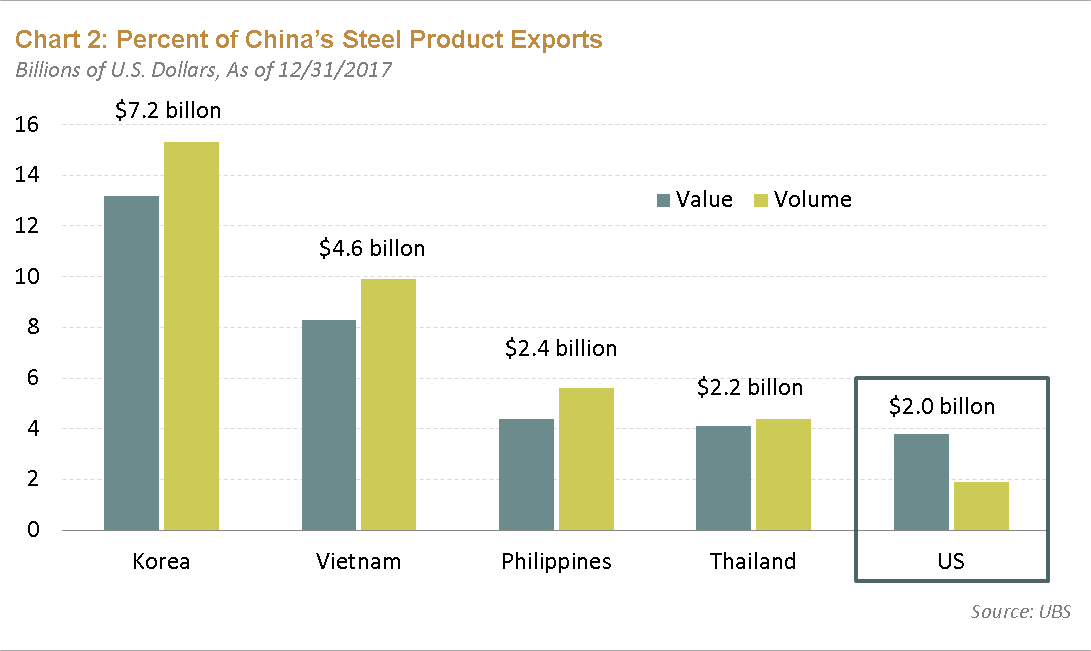

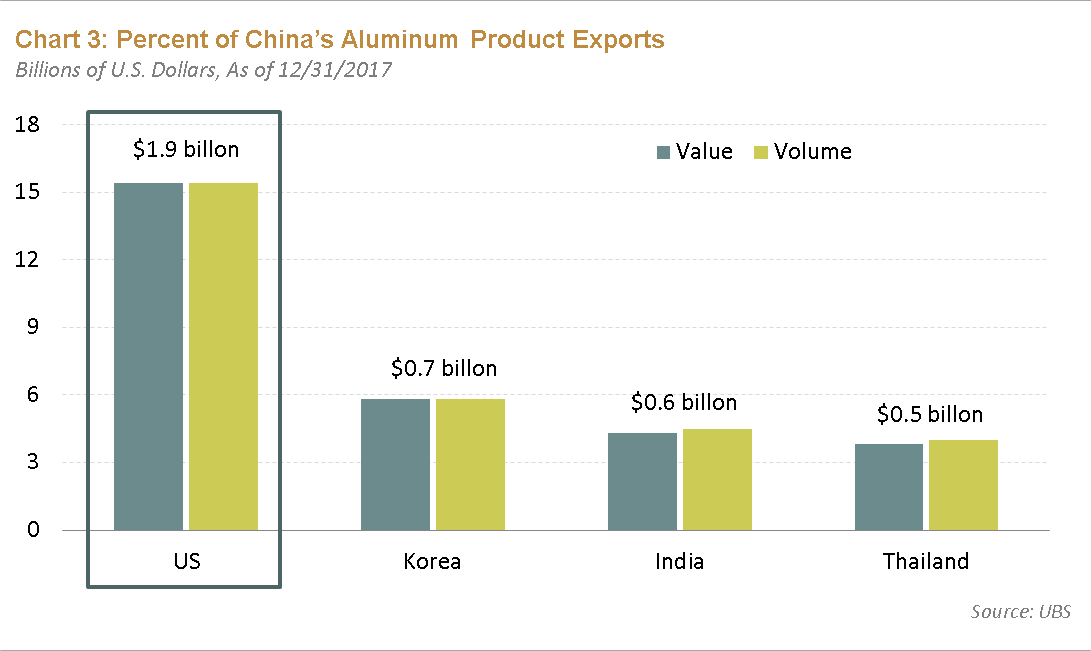

Furthermore, thanks to its excess capacity cuts, China has reduced its domestic steel production by over 200million (M) tons since 2015, with its export volume declining by one-third to 80M tons in 2017. As for aluminum, China’s exports to the U.S. accounted for 16% of its total aluminum exports in 2017. In sum, China exported $3.9 billion of steel and aluminum product to the U.S., roughly 0.17% of its total exports. Chart 2 and Chart 3 show the final destination for Chinese steel and aluminum exports:

However, there are three more important trends to look out for that indicate a storm is coming; we think they are not priced into markets:

- The unintended targets of a trade war

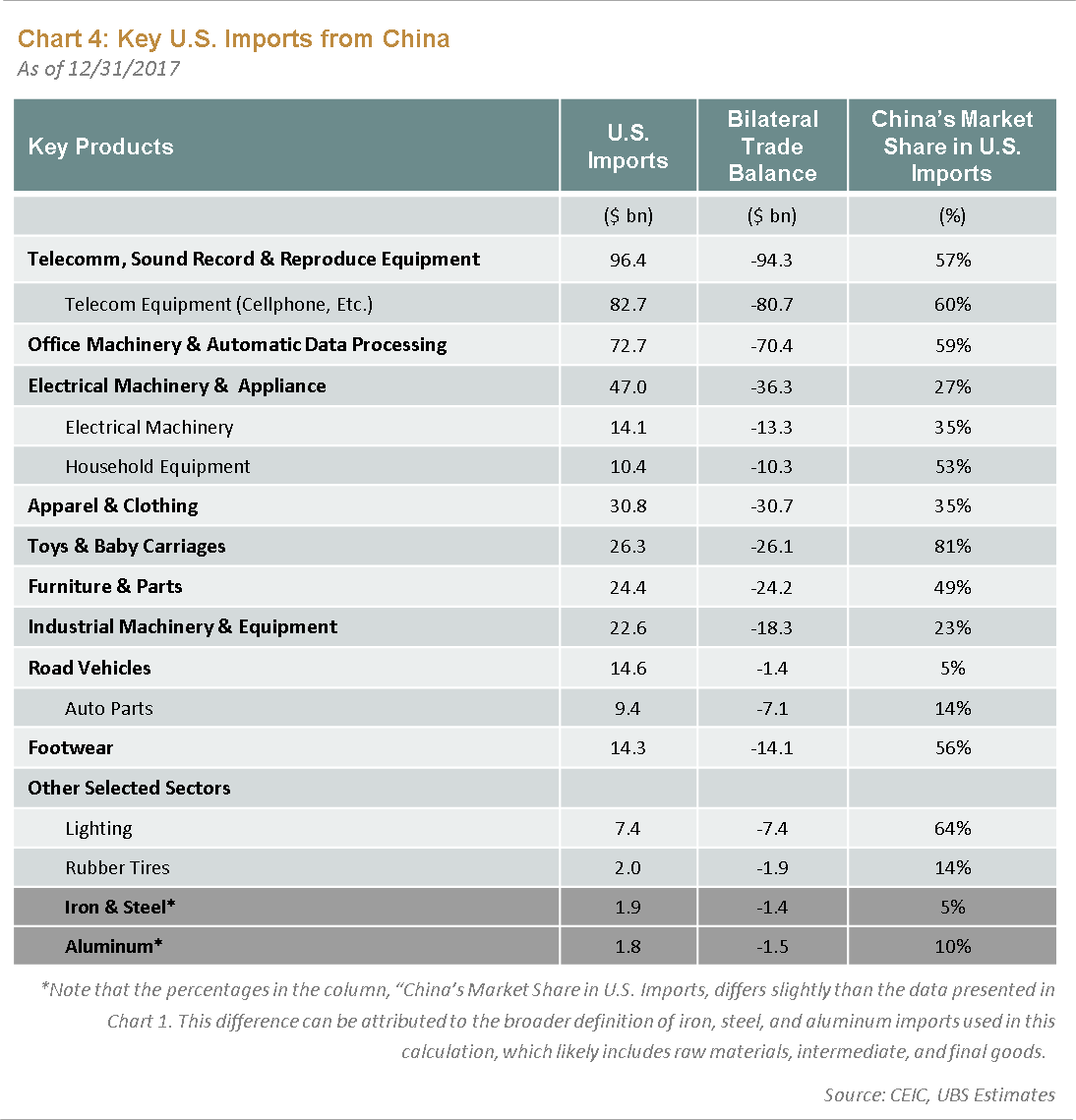

Even though steel and aluminum tariffs should not impact China in a meaningful way, it will impact some U.S. allies, despite Trump’s promise to provide exemptions for “real friends,” including NAFTA members, Canada and Mexico. Chart 4 below shows where the majority of the U.S. trade deficit with China resides. It is easy to see that if Trump wanted to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with China by $100billion (B), which is roughly one-third of the current +$375B trade imbalance, he should focus on industries in telecommunications (telecom), machinery and equipment, etc. Steel and aluminum contributed only $3B to the current deficit. Trump’s investigation of China’s theft of intellectual property is expected to conclude by August, or potentially as early as this April. By then, he might broaden the tariff to those bigger items with other protectionist measures like blocking foreign investment from China. By reversing the order and focusing on the smaller issue of steel and aluminum imports first, Trump risks the support of U.S. allies and jeopardizes a united front. If a trade war breaks out, it will not be just between the U.S. and China. More countries will be affected in today’s integrated global trade network; however, countries with less reliance on trade, such as India, could be better insulated from the effects.

- The end of engagement of China?

Over the past two decades, the symbiosis between the world’s biggest saver, China, and the world’s biggest consumer, the U.S., has worked its magic. Up until now, the relationship between the U.S. and China was more cooperative than competitive due to the large gap in terms of economic development. However, according to BCA Research, that symbiosis has deteriorated as U.S. households have been deleveraging after the global financial crisis (GFC) while China has been rebalancing away from its export model.

As the economic gap narrows, the pendulum has swung from cooperation to competition. The bilateral relationship between the U.S. and China has generally deteriorated, with the U.S. drawing comparisons between China and Russia as strategic rivals, and deeming China’s trade policies as predatory. The two countries have become competitors on many fronts, especially in terms of innovation, technology, and world influence. There is a discourse amongst U.S. policymakers on whether this is the end of a 40-year engagement with China, and whether all efforts to bring China into the democratic world order have failed. We can sense the general concern through Washington’s shift from using the term “soft power” to “sharp power,” a new political framework used specifically to describe Chinese and Russian policy. The U.S. views China as establishing a new world order by setting up alternative institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as a substitute for the World Bank. Additionally, new suspicions have arisen with regard to the huge scope and scale of Chinese influence within the U.S., which permeate American institutions of all kinds. For example, the backlash against the Confucius Institute, which helps Americans learn Chinese culture and language, is one case in point.

- Chinese diplomacy and potential response to a trade war

The removal of the “two-term” limit for the presidency and vice-presidency actually indicates that Xi has recognized the more hostile geopolitical environment and that China needs strong leadership with policy continuity to navigate through this atmosphere. The country is looking for one point person to deal with the diplomatic relationship with the U.S. and serve as damage control. That person could be Wang Qishan, the anti-corruption czar, or Liu He. A trade war is the last thing China needs right now. In its most recent National People’s Congress (NPC), China announced plans to open its manufacturing sector and improve market access to financial services, telecommunications, healthcare, education, elderly care, and electric cars. Contrary to Trump’s tariff hikes, Premier Li also promised to lower tariffs on automobiles and some consumer goods. China has made an effort to avoid a trade war but will respond accordingly if Trump’s protectionism ramps up. In return, China could buy less American goods, block investments, or sell U.S. Treasuries. On another geopolitical front, it is encouraging to see the U.S. make some progress with North Korea, which China has helped through its sanctions. If a trade war erupts, as a quid pro quo, China can reverse its stance and worsen the situation.

Conclusion

It is not the current tariff per se that will have an immediate and negative impact on global trade or economy, but the second-order retaliatory measures and deep-running adversarial trends in the world order that will have significant consequences. There is more to come on the trade tension between the U.S. and China. The accusations regarding intellectual property theft is a bigger deal to watch. Trump’s fiscal stimulus via a tax cut and the weakening dollar portend that the U.S.’s current account deficit will increase rather than decrease. A rising current account deficit will prompt Trump to be more aggressive in his protectionist measures, even though they are not the right remedial policy response. The drivers behind the U.S. current account deficit have deep structural issues. Protectionism is the wrong solution, especially in this complex post-globalization era; the result will be the disruption of a very integrated global supply chain, increasing friction of an already peaking global trade, reducing productivity, and the increasing risk of slower global growth.

The very fragile global economic recovery can be jeopardized, especially for the Eurozone and certain emerging markets, where trade contributed the most to its recovery. The dollar depreciated during “recent” historical protectionist episodes in the U.S., such as in 1971 during the Nixon administration and in 1985 during the Reagan administration, not only because the government used tariffs to depreciate the dollar, but also because of the effects of the end of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s and the subsequent Plaza Accord in the 1980s. Intuitively, protectionism should lead to a higher inflation rate, higher interest rates, and a potentially stronger dollar—which is not what Trump wants to see. The renminbi could also weaken if China retaliates as a way to defend its export share. In the event a trade war breaks out, spread assets and emerging market assets could sell off indiscriminately. However, a selloff could provide opportunities for value investors. The market has been complacent on this potential trade war, and therefore some caution is warranted.

Groupthink is bad, especially at investment management firms. Brandywine Global therefore takes special care to ensure our corporate culture and investment processes support the articulation of diverse viewpoints. This blog is no different. The opinions expressed by our bloggers may sometimes challenge active positioning within one or more of our strategies. Each blogger represents one market view amongst many expressed at Brandywine Global. Although individual opinions will differ, our investment process and macro outlook will remain driven by a team approach.

Download PDF

Download PDF