Numerous economic miracles have occurred across Asia, with China the most recent example. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2004 led to the country’s tremendous growth, helping to expand global trade and perhaps even contributing to the low rates of inflation experienced worldwide. Now, China, despite its current economic malaise, is advancing into another kind of economy, one that is less dependent on manufacturing and more driven by consumers and services. Success will be a tale told by time. The evolution of the Chinese economy begs the question: Which country succeeds China as the next transformational economy? Could India take the baton from China?

The Next Asia Miracle

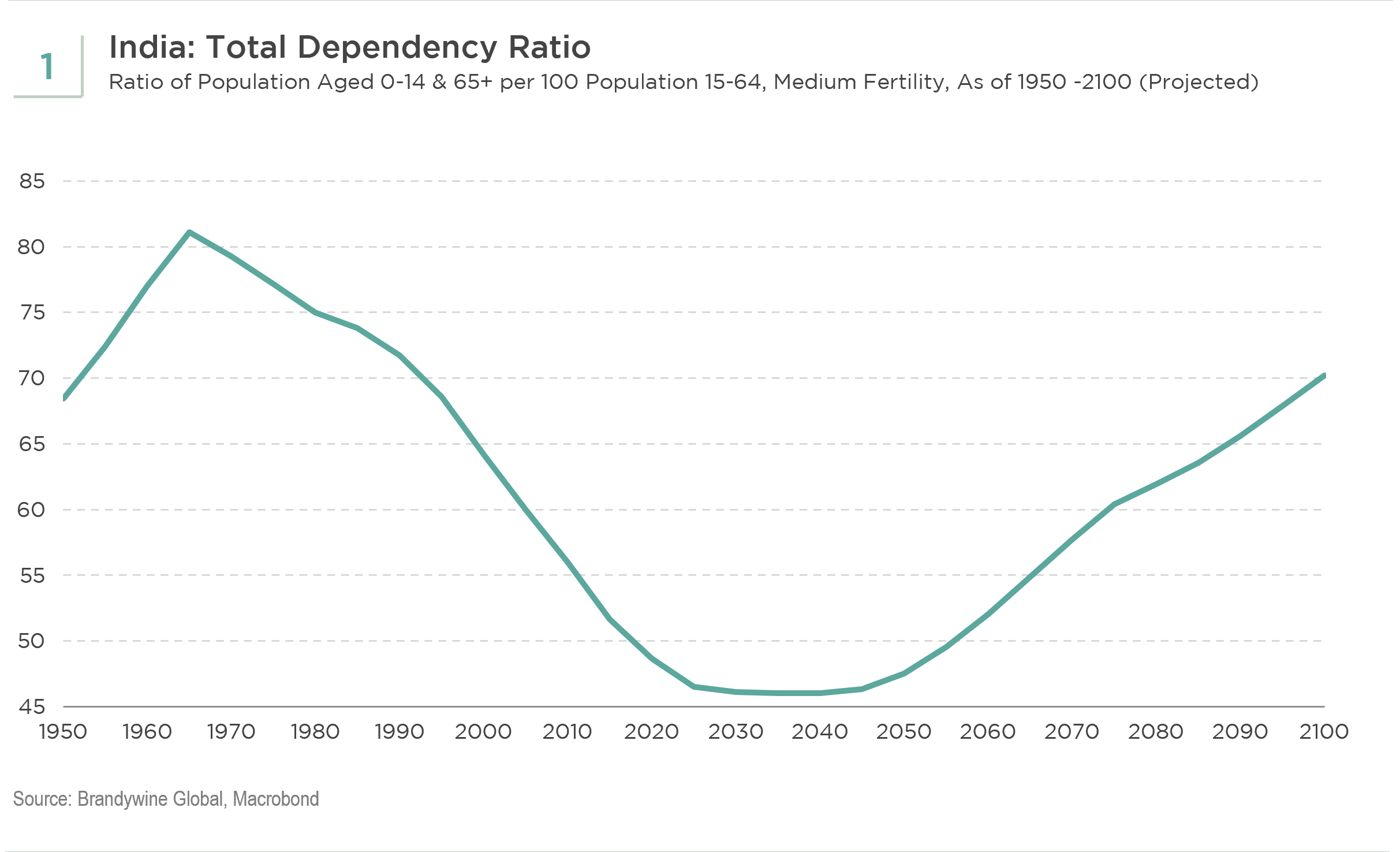

India could be the next China. India’s demographic advantage puts the country in a position to be one of the fastest-growing global economies—if not the fastest. India currently has a total population of 1.4 billion people, slightly less than China. By 2050, India is expected to have 1.7 billion people, becoming the most populous country. That population should mean that India’s economy could grow between 6-7% over the next 10 years. Furthermore, India’s population is young, as shown in its dependency ratio. India’s falling dependency ratio, indicates more active workers in the economy, supporting the old and the very young (see Figure 1). India needs to exploit this demographic dividend, but will it?

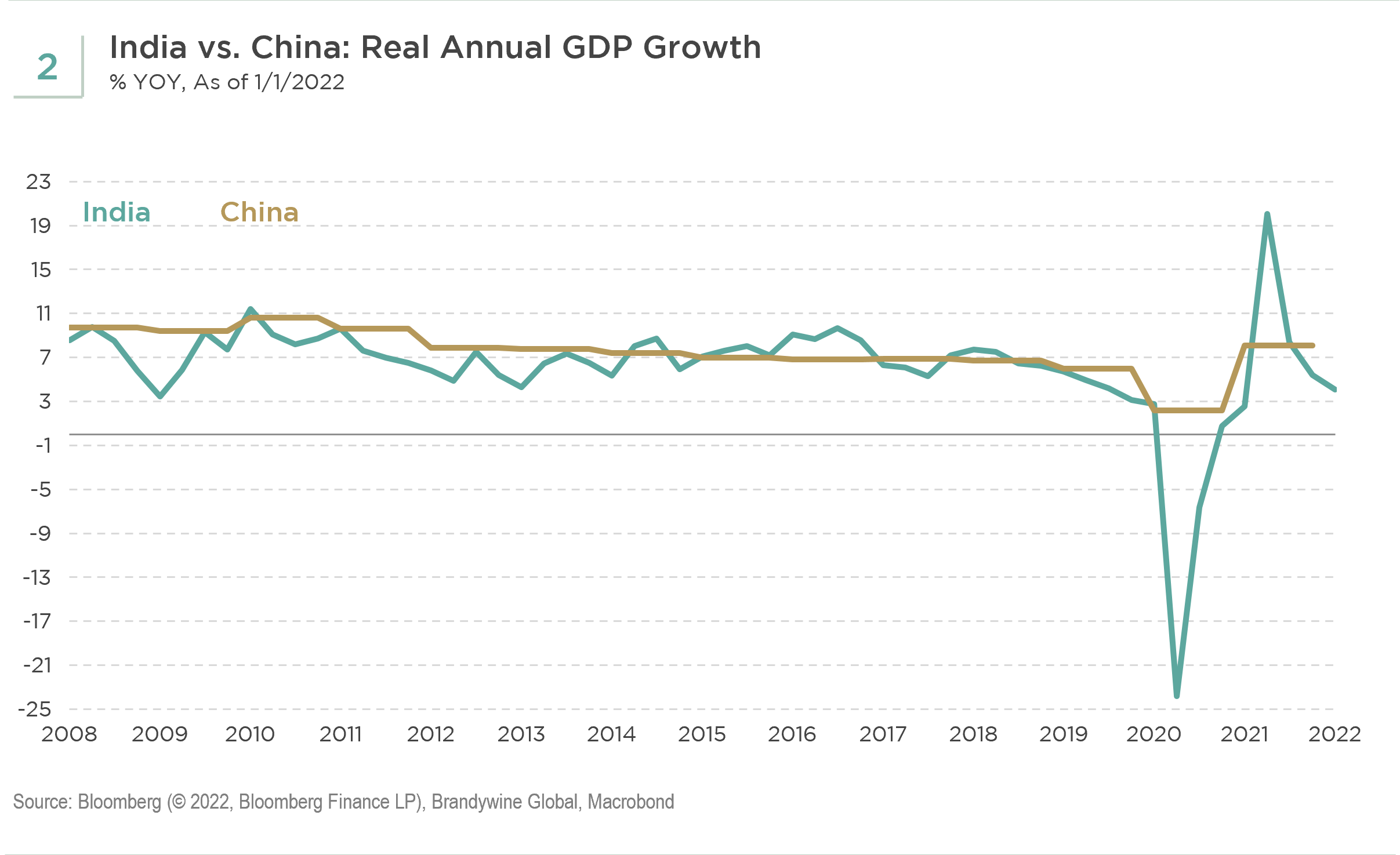

India’s growth rate has indeed been impressive, tracking China’s growth closely (see Figure 2). However, there is a speed bump developing, getting in the way of the pace of growth. India’s growth has not been fast enough to absorb workers into the labor force. Its unemployment rate is hovering around 7%, and the apparent lack of employment prospects has led to a drop in the labor participation rate. That drop appears to be more structural in nature, rather than simply the lack of employment opportunities as the economy moved out of the pandemic. This dislocation raises the question of whether India’s best economic days are behind it.

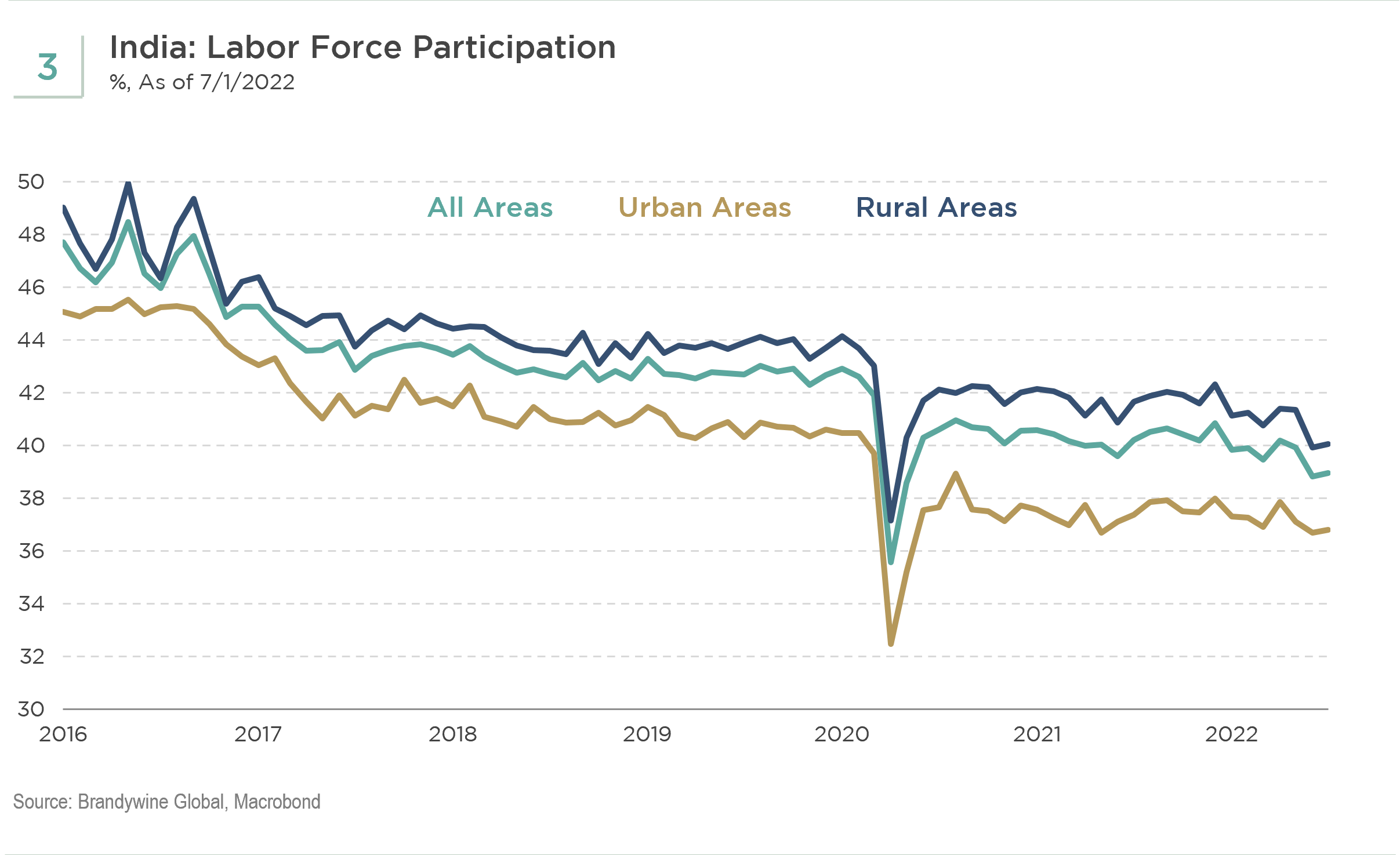

The available data indicates a trend of declining labor market participation as Indians exit the labor force. In 2016, total labor market participation was as high as 50% before beginning its descent to 39%. Understandably, the participation dropped sharply with the onset of COVID as the entire economy was locked down. There was a post-COVID rebound in the participation rate, but the declining trend resumed. Both rural and urban participation rates exhibit the same deterioration (see Figure 3). The trend in labor force participation is more negative for females.

Think about the labor participation rate for a moment. A participation rate of roughly 40% means that 60% of the labor force has either lost jobs or is no longer actively looking for employment. Additionally, India’s economy has become more focused on digitization and technology, which requires skills that are more scientific and a higher level of education and training. Lastly, there appears to be a lack of skills in the existing workforce for the digital and services-oriented economy that India aspires to become. Because the opportunities for low-skilled employment are lacking, India will be unable to exploit its apparent demographic advantage. To underscore this point, about 70% of India’s workforce has dropped out or returned to the informal economy, compared to Vietnam, which has an employment rate of over 70%.

India’s entree into high tech manufacturing and services has been well documented. The number of unicorns, referring to private companies with a value over $1 billion, has surged, a trend that is expected to continue. The government appears to have focused on high value-added manufacturing and eschewed the low value-added manufacturing that helped boost China as it developed and other Asian economies, like Vietnam. Low value-added manufacturing is labor intensive and does not demand a high skill level. India wants to leapfrog the labor-intensive production and jump right to the high value-added stage. No doubt India has been successful in supporting tech development, with Bangalore obtaining the moniker of the “Silicon Valley of India.” Nevertheless, the broad labor force is skill deficient. India ranks 131st out of 189 countries in the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI), behind countries like China, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

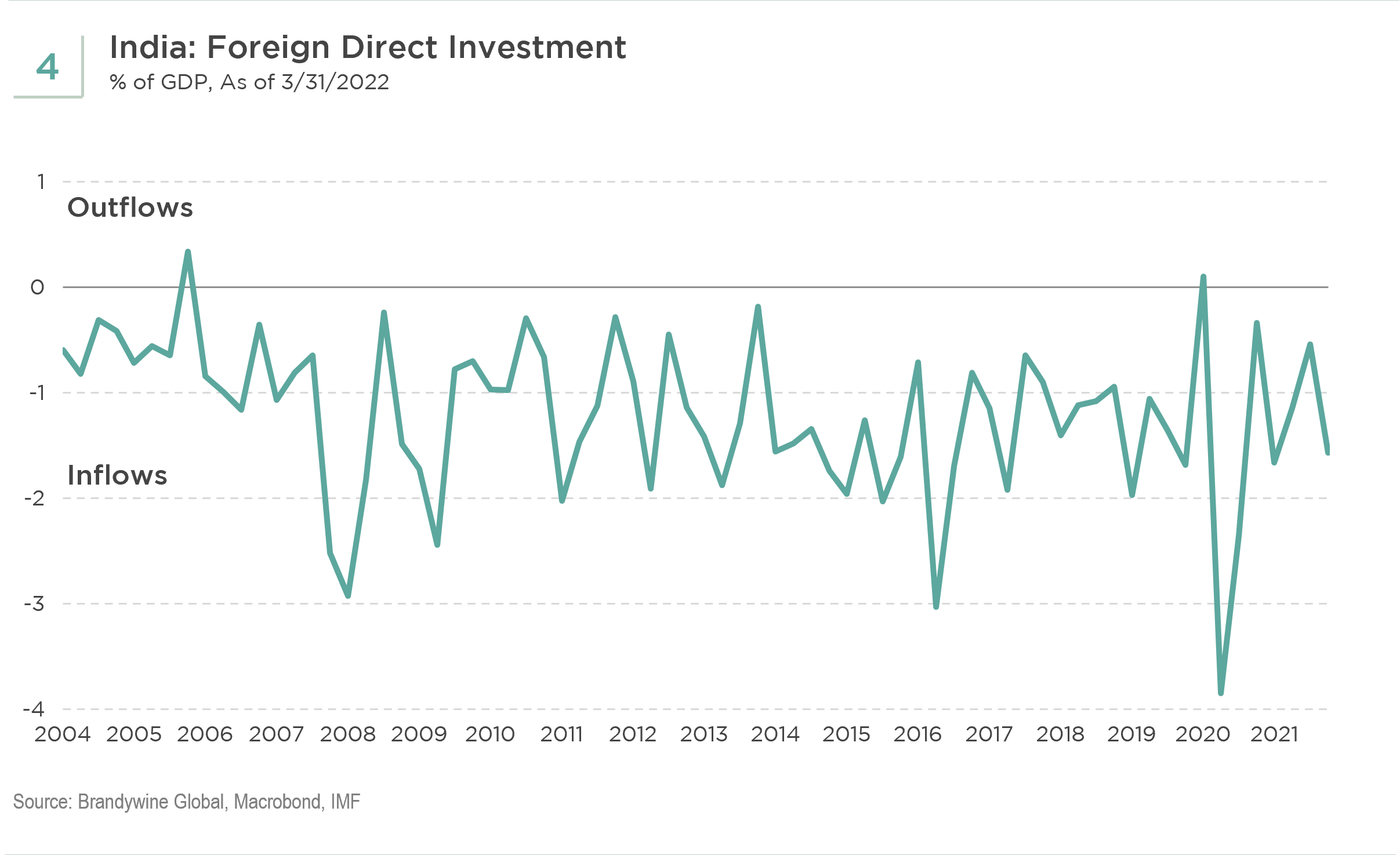

The growing tech sector has attracted foreign direct investment (FDI) to India (see Figure 4). However, this type of manufacturing requires highly skilled workers, a supply that is largely absent in an economy where 80% of the workforce is informal, working in either agriculture or construction. Moreover, manufacturing remains a relatively small part of the Indian economy, about 14% of gross domestic product (GDP), while China tips the scales at 27% of GDP. In sum, India lacks light manufacturing, appearing to have abandoned it to countries like Vietnam. This kind of labor-intensive production could have absorbed Indian workers, but the time may have passed for this source of growth.

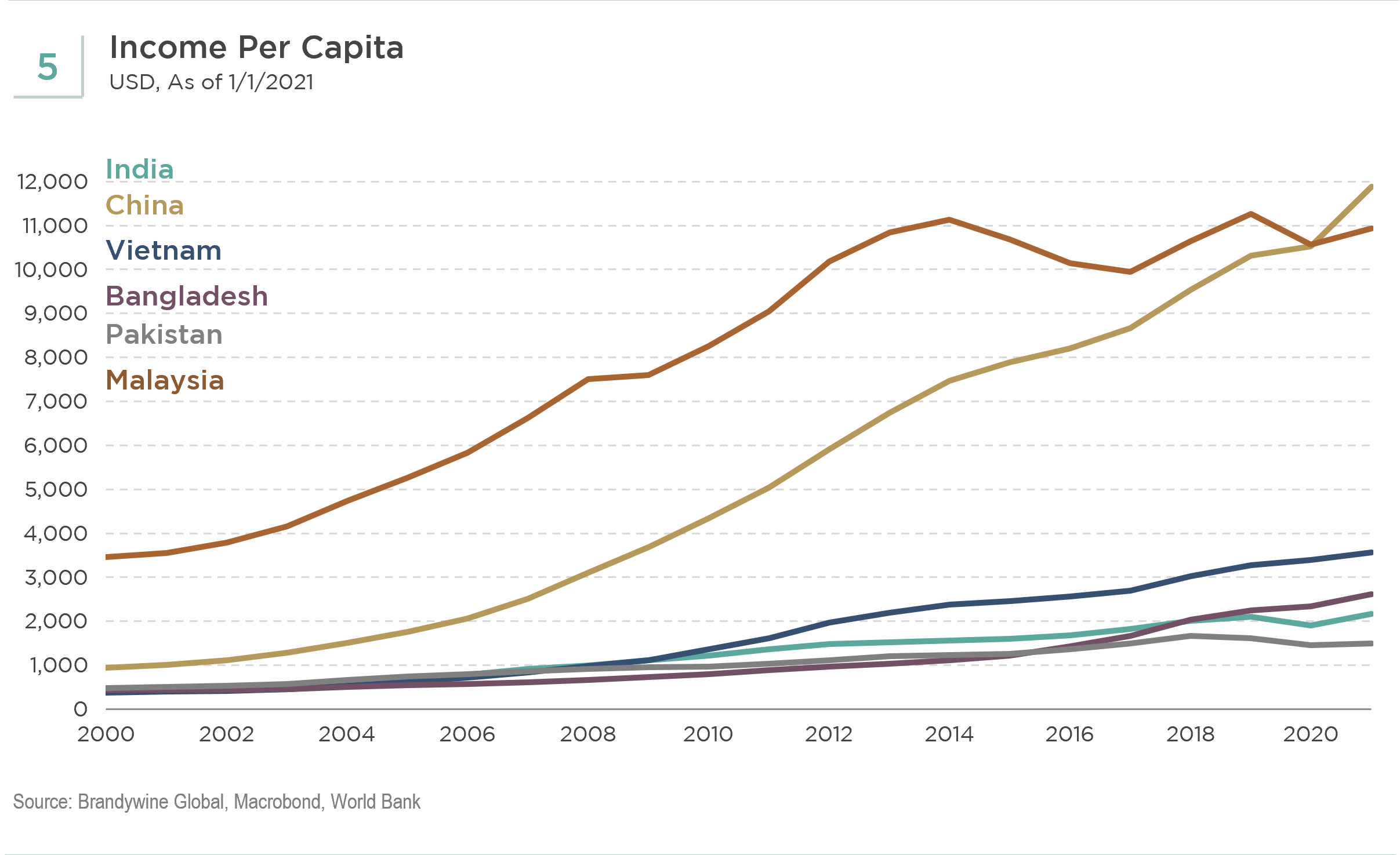

India appears to have taken itself out of the labor-intensive manufacturing sweepstakes. Instead, the government wants to develop its manufacturing sector to grow the economy and put Indians to work. As noted, it has abandoned low value-added manufacturing and left that to countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam. These neighboring economies have benefited from this kind of manufacturing, which appears to have boosted their per capita income. Vietnam has a per capita income that is 38% higher than India’s. Bangladesh has a higher per capita income, too. These countries have become home to many textile and clothing manufacturers and have seen exports skyrocket. Countries that have sought labor intensive manufacturing also have much higher labor force participation rates than India. Figure 5 shows India trailing many of its neighbors in national income per capita.

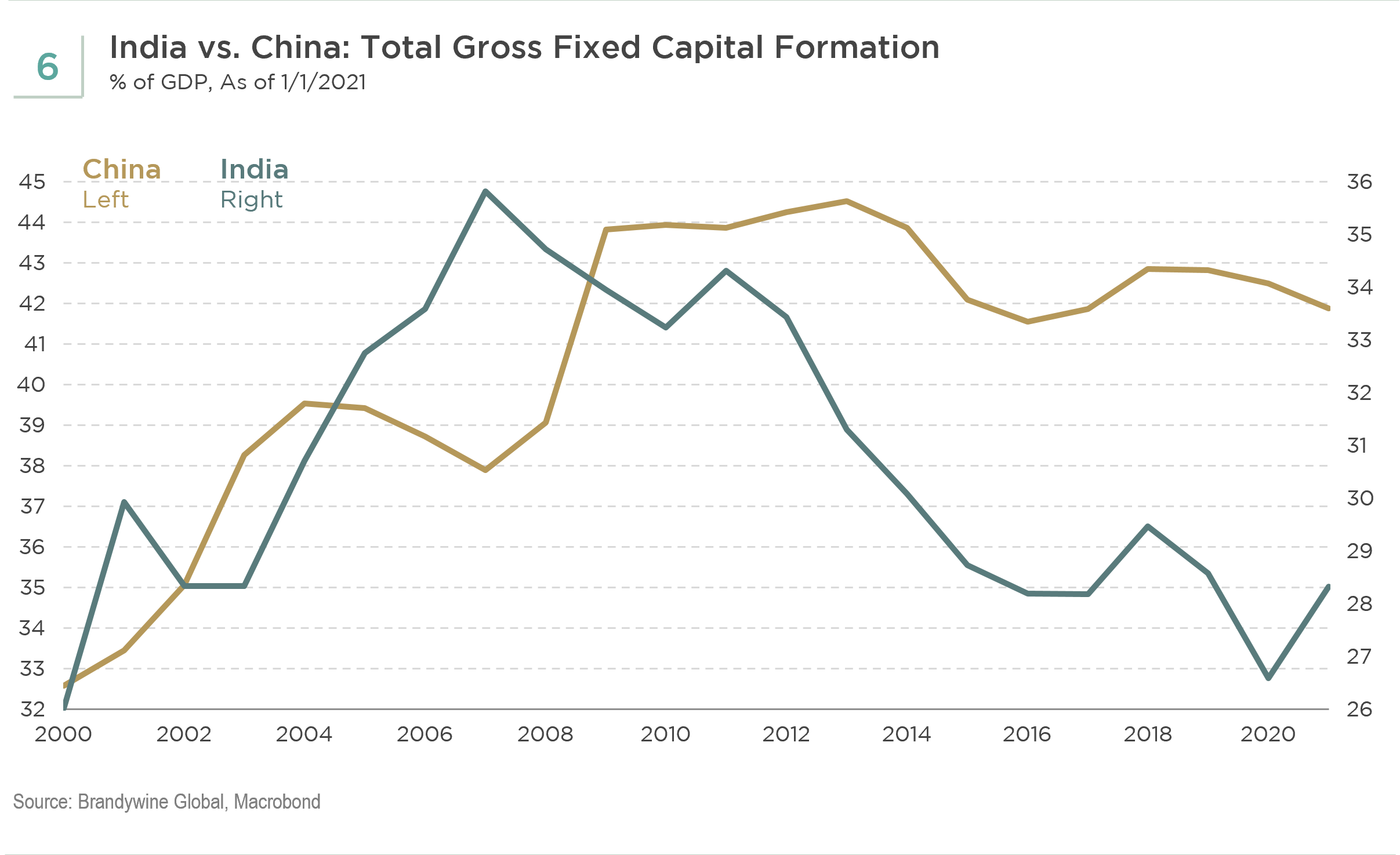

Additionally, India needs to invest to grow its capital stock and improve productivity. Figure 6 depicts capital spending, comparing India’s investment spending to that of China. If China’s investment rate is the goal—and it should be—India falls woefully short. China’s gross capital formation is about 42% of GDP. India’s is less than 34%. To grow the economy and boost productivity, India needs to step up investment’s share of GDP. Additionally, the government must boost capital spending on infrastructure, on which businesses depend. However, India is an insufficient saver. It runs a current account deficit. To boost its capital formation’s share of GDP, India will have to continue to attract foreign direct investment.

Conclusions

- India is not likely to become the next China. The story, though, remains complicated, and the efforts to grow India’s economy should address exploiting its young demographic.

- India’s fast growth phase is behind it. Even if the country desired it, it is probably too late to attract light manufacturing, manufacturing that could bring lesser-skilled workers into the labor force as it has in places like Vietnam.

- Labor force participation rates remain low. Economic growth will require a rising labor participation rate. The growth engine in India continues to be in high tech and IT services, but there remains a paucity of skills that can easily move into production that is more scientific and knowledge based. The government needs to emphasize educational improvements.

- India remains synonymous with entrepreneurship, especially for technology firms. The tech sector is expected to grow at twice the rate of the overall economy and be a growing contributor to IT service exports. Digitization will continue to be an overarching theme for the Indian economy, bringing new investments in education, government procurement, and banking, among many activities. This remains the country’s bright light.

- Both private and government investment need to accelerate to help drive the economy forward. Government investment should support business investment spending. The government should continue to implement reforms that include bankruptcy, land, and taxation. Selling state-owned assets could be a source of funding for infrastructure development.

- The renewable energy transition could provide an opportunity for the low-skilled worker, boosting the economy’s growth rate. India has ramped up its renewable investments, leading to record renewables investment in the last fiscal year. Rising demand and lower prices should propel renewables-related manufacturing. The Narendra Modi government has announced a green hydrogen policy, providing tax breaks and land to build plants for green hydrogen using solar energy. Some foreign companies are partnering with Indian businesses to produce renewable energy.

Groupthink is bad, especially at investment management firms. Brandywine Global therefore takes special care to ensure our corporate culture and investment processes support the articulation of diverse viewpoints. This blog is no different. The opinions expressed by our bloggers may sometimes challenge active positioning within one or more of our strategies. Each blogger represents one market view amongst many expressed at Brandywine Global. Although individual opinions will differ, our investment process and macro outlook will remain driven by a team approach.

Download PDF

Download PDF