- The first offender has to be the dramatic slowdown in the nominal growth rate of China, from over 20% in 2011 to less than 6% more recently (see Chart 1). The developing world has generated over 70% of the global economy’s incremental expansion in the last 5 years or so, and China has been the major contributor to that growth. Naturally, this kind of epic growth slump was destined to be felt around the world.

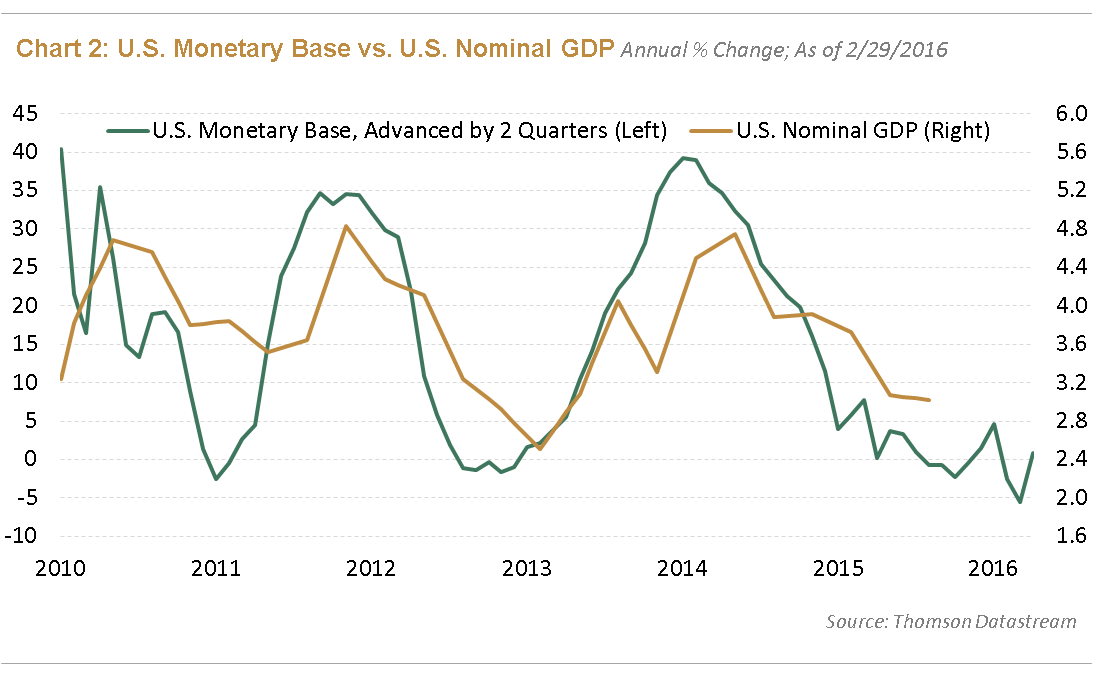

- The second contributor to the story has been the timing of the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) move to renormalize interest rates. A 25 basis point rate hike seems trivial in isolation, but takes on added significance when one considers that we live in a zero-bound world where nominal growth has been scarce. The Fed policymakers chose to dismiss the surge in the U.S. dollar and, until recently, the widening in corporate bond spreads as signals that liquidity conditions might actually be less expansionary than they think. In contrast, the slide in the growth rate of the monetary base has done a reasonable job of predicting the near-term trajectory of nominal GDP growth (see Chart 2).

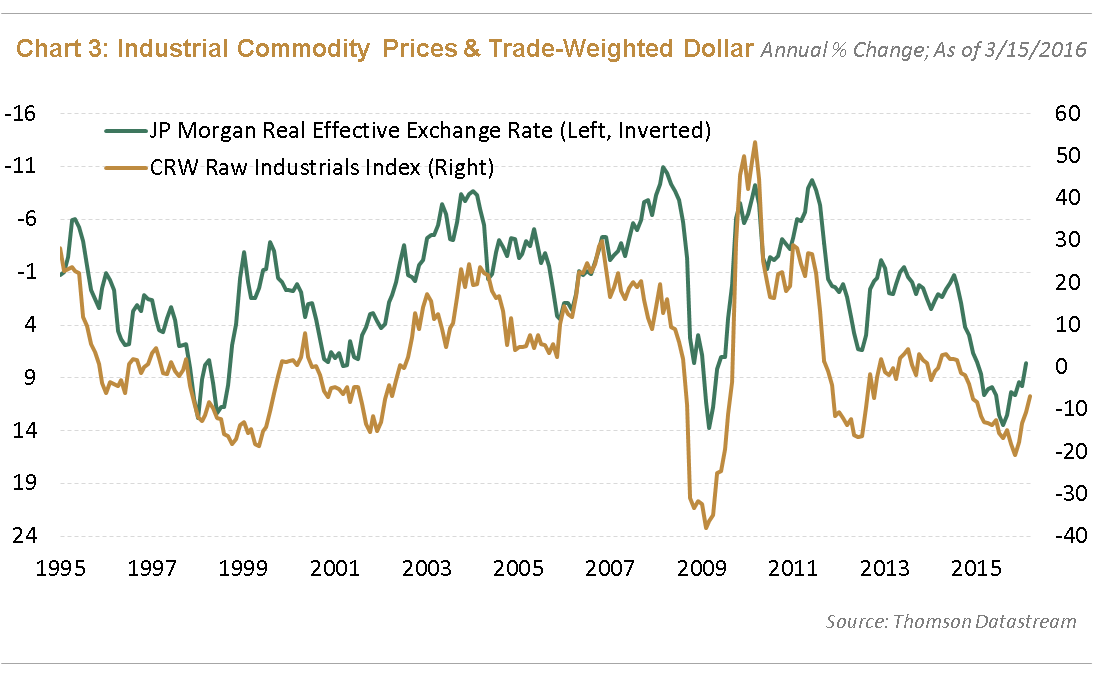

- Lastly, dollar strength has created a global nominal dollar shortage. If there was only one global central bank, monetary policy would have been expansionary the past two years. Instead, the dollar—which is the de facto global reserve currency—has become scarcer. Dollar strength imports external deflation to the domestic U.S. economy, restrains corporate pricing power, and hurts profitability. Correspondingly, weak emerging market currencies (EM) encourage central banks in those countries to raise interest rates because of inflation pass-through worries. It is impossible to disentangle dollar strength from commodity price weakness (see Chart 3).

Something Had to Give

These deflationary forces reached the breaking point in the second half of 2015, based on the slide in the S&P 500 Index and oil prices. When the Fed balked on rate hikes in September, the index bounced back. However, share prices subsequently plunged and oil dropped below $30 when the central bank signaled its intent to forge ahead with renormalization. In the background, China’s efforts to contain the weakness in the yuan caused the People’s Bank of China’s balance sheet to contract. Meanwhile, the dollar was hitting new highs, albeit against a narrowing basket of mainly emerging market currencies.

Debt deflationary anxiety reached a fever pitch with the onslaught of January’s volatility. Energy stocks were as discounted as financial stocks were in early 2009, corporate bond investors had priced in a recession, and U.S. bank stocks were priced for some significant balance sheet destruction. Something had to give, and from the reaction in February and into March, the shift has been clearly in the direction of reflation.

Noticeable Shifts on Three Fronts

First, Chinese economic policy has become geared more to short-term economic support and less toward long-term reform, at least based on an assessment of the February G20 meeting and the more recent Government Work Report. The authorities seem to acknowledge the mutual inconsistency of a stable currency, expansionary monetary policy, and free capital flows. The remedial response so far has been to step up fiscal support for the economy, boost credit growth on a selective basis, and cautiously expand monetary policy. The measures sound good at least for the short term. However, they do not really address the longer-term problems that have driven China’s slumping nominal GDP growth—excess industrial capacity, profit-losing state-owned enterprises (SOE), and the build-up of loans to this group of companies. China’s leaders are obviously worried about the labor market implications of bankrupting non-performing SOEs. While they seem prepared to put a bandage on the problem by throwing more credit at it in the near term, they appear to be avoiding performing any radical surgery which would include recapitalizing the banks with a big TARP-like refinancing scheme. However this story plays out, it is hard to believe that the Chinese authorities will lose control. A more likely scenario is that financial liberalization could take a step back as the authorities gravitate toward their comfort zone of tighter control.

Second, the Fed has again balked at the pace of interest rate normalization. Several Fed Governors have expressed concern about deteriorating inflation expectations, both market- and survey-based, given the mixed U.S. data. The labor force data show solid employment gains and rising wage growth. However, front-leading indicators of activity like the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) indexes point to economic deceleration. Real GDP growth seems to be holding around 2% with nominal GDP growth not much higher. The dovish pivot by the Fed was confirmed by the March Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announcement and the ratcheting back of the Fed’s interest rate dot plot.

Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, the dollar has been soft. Correspondingly, the dollar’s twin sister, commodity prices, bottomed last November. This development may be a good example of “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop,” a truism originally proposed by the late Herbert Stein, former chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Nixon Administration. In our view, another 10% surge in the U.S. dollar, under current economic circumstances, would be extremely negative for global growth. Capital markets generally act to support non-inflationary economic growth. In this instance, it seems the dollar has started a kind of autonomous correction/sell-off aimed at helping shore up global activity. The dollar actually peaked against the major currencies as early as the first quarter of 2015. Moreover, as the deflationary pressure has risen to a peak, the breadth of the dollar’s rally has fallen off with currencies like the Brazilian real, bottoming as early as last September. The Mexican peso, standard bearer in some ways for EM foreign exchange rates, recorded a recent low in early February 2016 when the overall global risk environment really started to shift.

Some Conclusions

The odds seem to favor a bumpy shift to reflationary trends gaining the upper hand this year, and the first quarter of 2016 could turn out to be the inflection point. So far, there is no objective data to confirm this viewpoint. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) leading economic indicator recently made a new low. China’s economic data has been skewed by New Year’s celebrations and the corresponding work holidays and market closures. The February labor force report in the U.S. was strong, but the services Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) was very weak, with the employment category especially soft.

The obvious downside risks are that the Chinese fail to add enough stimulus, or that the Fed shifts back to the status quo too soon, or worse, engineers some kind of a dollar shortage through continued shrinkage of its balance sheet and monetary base.

On the plus side, the narrowing in U.S. corporate spreads is a clear indication of some kind of turning point, something not seen in the previous two years. In addition, the global economy has entered the sweet spot in terms of the long and often unpredictable lag time between a major drop in energy prices and an improvement spending and growth. Policymakers are more worried about not providing enough stimulus rather than giving too much.

We believe any reflationary uptrend is going to be bumpy. Core inflation in the U.S. is beginning to creep up largely on the back of cost-push pressures from the labor market. Meanwhile, core inflation in Europe is holding steady at nearly 1% despite the European Central Bank’s concerns about deflation. Monetary policy is hardly likely to do a U-turn anytime soon given all the rhetoric about secular stagnation, the slump in nominal GDP growth around the world, and tail risk worries about declining growth in China or a surge in the dollar. However at some point, interest rate expectations could advance more quickly as stability/strength in commodities, corresponding weakness in the dollar, and reflationary policy measures begin to shift the mindset of investors away from concerns of deflation.

Groupthink is bad, especially at investment management firms. Brandywine Global therefore takes special care to ensure our corporate culture and investment processes support the articulation of diverse viewpoints. This blog is no different. The opinions expressed by our bloggers may sometimes challenge active positioning within one or more of our strategies. Each blogger represents one market view amongst many expressed at Brandywine Global. Although individual opinions will differ, our investment process and macro outlook will remain driven by a team approach.

Download PDF

Download PDF