- In the second part of this series, we review the factors that could contribute to a decline in global growth.

- While the fed funds rate remains low relative to history, the pace at which the Federal Reserve raised rates, along with quantitative tightening, may have tightened conditions too quickly.

- Latent wage and inflation pressure in the U.S. and other OECD economies may render future central bank easing ineffective.

- Financial and economic conditions in China, including flagging M1 growth, credit growth, and a dwindling current account surplus, may offset a more sanguine outlook on the Chinese and global economies.

The Bearish View of the Global Economic Cycle

Federal Reserve Policy

A good place to start evaluating the bearish case for global growth is to consider policy changes at the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed). As we know, the Fed raised interest rates by over 200 basis points (bps) over the last few years—by a variety of measures, that's pretty substantial. We know interest rates have declined structurally over the past 40 years through multiple cycles; so, one way to think about how monetary tightening matters on a cyclical basis is to consider how much rates have risen relative to the past 10 years. On this basis, the Fed tightening cycle is cause for concern. Five out of the last six recessions were preceded by a similar increase in the real fed funds rate relative to its longer-term average. Admittedly, the level of interest rates, particularly in real terms, does not appear onerous. And yet the ongoing debate among Fed officials and economists on what truly is the “neutral” level of interest rates suggests there is considerable uncertainty on this issue. Meanwhile, history suggests changes in interest rates have a material effect on the economy.

Quantitative Tightening

The Fed has recently communicated that it is not going to reduce its balance sheet as aggressively as previously indicated. However, the scale of quantitative monetary support to the financial system and the global economy is still significantly lower than it was two years ago. There's much debate as to how much quantitative easing actually supported growth, but assuming the policy had some impact, the substantial decline in quantitative support might also indicate that a recession is more likely over the coming months.

The Phillips Curve

We should also evaluate the current Fed tightening cycle within the context of labor market slack. Unlike 2016, when the Fed paused on interest rates, unemployment in the U.S. is much lower today. And it's also not just the U.S.—the unemployment rate across the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) members is much lower than it was back then. These low unemployment rates matter because they may indicate latent pressure for wages to accelerate further in the U.S. and other parts of the world. As such, wage pressure may limit the degree to which inflation can decelerate cyclically. In turn, this may limit the ability of the Fed and other central banks to lower interest rates in the face of weakening growth rates. This kind of misstep is typical of the Fed during the later stages of the cycle: it stays too tight for too long because of latent inflation and wage pressure, and the U.S. economy therefore falls into a recession.

U.S. Lending Standards

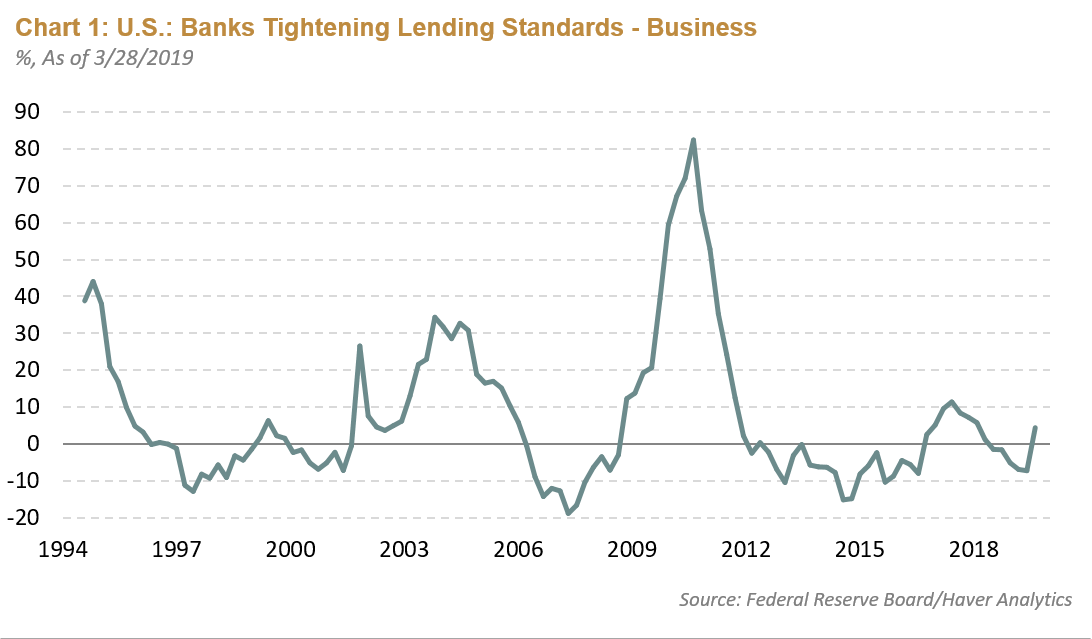

It’s also worth noting the effect that monetary policy has had on U.S. lending standards. The Fed's Loan Officer Survey suggests banks have tightened lending standards to a variety of borrowers across the country. And since monetary policy works with long and variable lags, we may not have yet seen the full impact on the banking system from the Fed’s policy changes over the past two years. Meaning, lending standard may tighten further (see Chart 1).

The rise in delinquencies related to the increase in credit card interest rates also suggest that Fed tightening is having a more pervasive impact on the economy. In part one of the blog, I mentioned that the U.S. corporate sector had issued a lot of debt in the last decade, but the household sector and banking system were in better shape. In the household sector specifically, I noted that the debt-service-to-income ratio (how much of household income is being used to service debt) is at multi-decade lows. At face value, this would suggest U.S. households have room to increase borrowing and sustain consumption. However, we also know that income inequality in the U.S. has steadily risen. And so, if we consider the median household instead, one can arrive to a different conclusion. Mortgage payments, as a share of median income, have actually risen meaningfully in the last few years. This increase might suggest that that the household sector is more vulnerable to a retrenchment in the current environment than some of those other average numbers would otherwise indicate.

China

Money Supply Growth

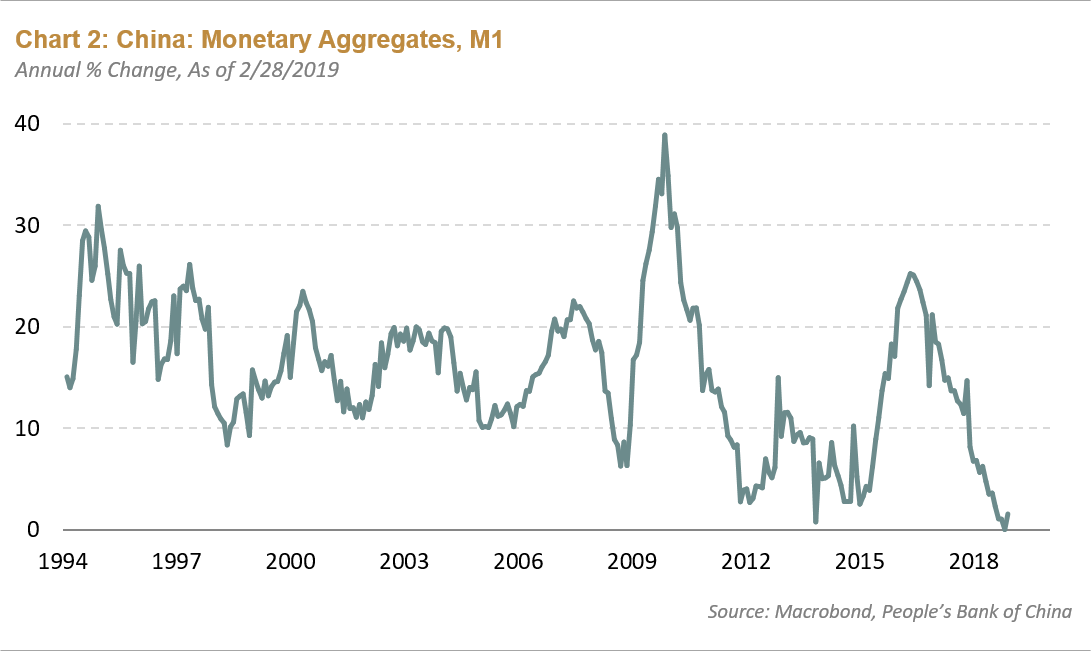

Understandably, the topic often turns to China when determining whether a global recession may be coming. Given both cyclical and structural drivers of the economy, and the seemingly conflicting policy goals, it can be difficult to assess what the Chinese are doing in terms of monetary and fiscal policy. However, the material deceleration in money supply growth is definitely cause for concern. Chinese M1 recently decelerated to the weakest rate of growth in nearly two decades. Given the strong relationship between money growth and nominal activity in China, this data suggests the country remains in the midst of a material economic slowdown. While Chinese authorities may be publicly indicating that they're easing policy by certain measures, it's not showing up yet in money growth (see Chart 2).

Credit Growth

The significant expansion of credit growth and debt levels in China over the past decade are also reasons to be concerned about the economy. History suggests there is an eventual reckoning when countries expand credit rapidly. The Chinese may be able to manage this adjustment given their substantial domestic savings base and the relatively closed nature of the balance of payments. Moreover, the Chinese have reversed their more recent restrictive policies towards credit creation—so the financial and economic stress may have diminished for now. However, easing credit policies may also have a more muted impact on growth today. By some estimates, the share of credit creation used largely to service existing debt obligations has increased, which weakens the effectiveness of easier monetary policy. China may need more monetary easing over a longer period of time before the economy improves.

The External Balance

China’s external balance—its current account and trade balances—has markedly diminished from where it was in the mid-2000s. Back in 2005, the current account balance in China was nearly 10% of gross domestic product. This high watermark for the balance matters because since then, every time the Chinese wanted to ease monetary policy, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) could do so without necessarily weakening the currency due to the enormous surplus. Today, that current account surplus is basically gone so when the PBoC eases monetary policy, the renminbi is more likely to weaken. The weaker currency conflicts with the trade negotiations that are underway between the U.S. and China—a significantly weaker renminbi could undermine those negotiations, limit what China can do in terms of monetary policy, and ultimately cap the country’s economic recovery.

How Are We Thinking about Global Growth in Our Outlook?

We believe global growth continued to decelerate through the first quarter of 2019. We expect the global economy to stabilize at low levels in the second quarter before more visible signs of economic improvement—led by China—become apparent in the second half of this year.

Ultimately, we think a global recession this year is unlikely and the policy easing underway in China is a material part of that projection. The recent shift in Fed policy should also reduce the risk of a recession; the central bank has moved very quickly from where it stood at the end of last year. While the Fed’s pivot has not yet telegraphed a cut to the fed funds rate, we think it's possible that it could head down that path quickly if U.S. growth weakens further. The nimble response from these two particular central banks should diminish the downside risk and clear the way for a more constructive outlook on financial assets. We’ve seen this view start to play out in the equity market but is likely to extend to other markets as well—especially in the fixed income, corporate, and emerging market sectors. Within this context, we are constructive on both U.S. Treasuries and emerging market fixed-income securities.

Groupthink is bad, especially at investment management firms. Brandywine Global therefore takes special care to ensure our corporate culture and investment processes support the articulation of diverse viewpoints. This blog is no different. The opinions expressed by our bloggers may sometimes challenge active positioning within one or more of our strategies. Each blogger represents one market view amongst many expressed at Brandywine Global. Although individual opinions will differ, our investment process and macro outlook will remain driven by a team approach.

Download PDF

Download PDF